LAUREN MOYA FORD

Often times when you befriend someone you have the luxury of knowing what their favorite ice cream flavor is, how they drive their car or when they get off work each day. I'll be totally honest with you, I don't know these things about Lauren Moya Ford. But I would say I know her in a very special way. In my last semester at University of Houston (UH), I enrolled in an art history course called Mexican American Art + Politics. As I walked into a classroom full of graduate students, both trained art historians and practicing artists, I became intimated with the fact that I was the youngest person in the room and I was only one of the few undergraduates. I took a seat at the table and started introducing myself to the people around me. Luckily, next to me sat Lauren. I was excited because I had heard so much about her unique work. It took me awhile to realize how alike we actually were. In between our class discussions on our favorite Selena music videos and the socioeconomic issues surrounding the border, I was able to get to know Lauren on a deeper level. Turns out that we both grew up in the same neighborhood in Austin, attended the same Catholic church in Oak Hill and my brother even went to school with her.

Over the years I have followed her creative projects and international travels both in Houston and beyond. Her recent lecture, Fabiola, was held at the Menil Collection this past summer and it completely enthralled me. Both prophetic and melodic, Lauren took the time to notice, appreciate and value the little things that have defined her own personal faith journey. She recognizes that she is human. A Spanish "dicho" that I've been exposed to is "dime con quién andas, y te diré quién eres" or in English, "tell me who you walk with and I will tell you who you are." Something that Lauren embraces daily. Personally this also guides my life's decisions and provides a road map to my growth. Being human we have our short comings and our triumphs, Lauren exemplifies our humanity through living these virtues. After watching her presentation and seeing her work for years, I decided it was time to understand her creative processes and expressions on a larger scale. For your consideration, I've included her lecture and script with our interview below. Escucha con tu corazón abierto.

I love that we are both from Austin and that we met in Houston at UH. How has leaving your hometown changed you? What is it like coming back to Austin after so many experiences?

LMF: Living here feels new, but in some ways it’s also bringing me closer to home. My grandfather Luis Moya, a Mexican-American World War II veteran, worked as a translator here in the 1950s and 60s. Growing up hearing my mom’s stories about her childhood in Madrid made me want to live here for a long time. I think about her and her family a lot when I walk around the Prado and other places they used to go, and I happen to live around the corner from a place where my grandfather (who I never met) worked. So it's strange and beautiful to be here, foreign and familiar. But Texas stays on my mind, and I appreciate home more. I miss my family, and I understand why people hold onto their music and food no matter how far away they go. I love Madrid, but I miss tacos every day!

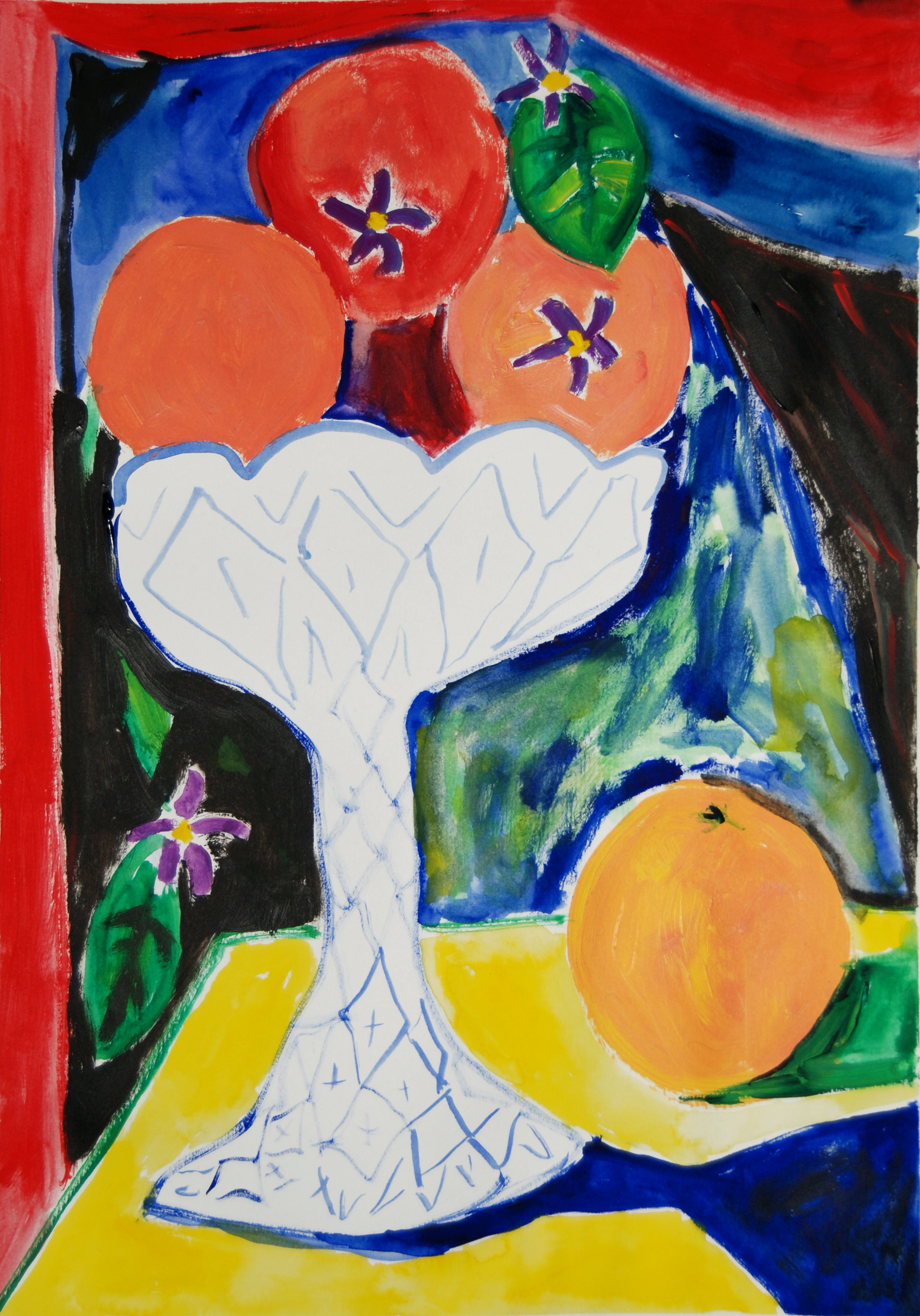

New Hands on Old World Flowers, 2016, Big Medium

Speaking of going back to Austin, you recently presented your latest solo exhibition, New Hands on Old World Flowers, this past summer at Big Medium! Congratulations. It looked lovely and I was very sad to miss. I would love for you to speak on the collaborative aspect of this. You worked with a photographer Brenda Cruz Wolf, ceramicist Jessica Ninci and another collective The Center for Imaginative Cartography and Research. What was the motivation behind the exhibition? Was the idea there before the collaborations or was this show something you all wanted to accomplish together?

LMF: New Hands was a way to process the time I spent in Galicia, an autonomous community in northwestern Spain. Galicia is so special. Its landscape is dominated by dramatic coastlines and deep forests enshrouded in rain and mist. Its culture is very distinct from the rest of the country. People there speak another language (Galician), celebrate different holidays, and the traditional music is played on a bagpipe called the gaita. Galicia was the context for my first experience living abroad, with all the highs and heartbreaks that come with it. So the show was a way to work out the time I spent in that mystical and mysterious place.

Friends are essential to the way I make work; I admire and am inspired by what they do. If I have an idea for a piece but I don’t have the expertise or materials to execute it, I rely on my friends to help me. The ideas that emerge from this collaboration enrich the project immensely. This is also true in the curation phase- Kevin McNamee-Tweed, the curator of New Hands on Old World Flowers, brought a ton to the table.

I love your blog, Vigo Expo! What was the motivation of starting this? What have you learned from blogging while traveling?

LMF: I started writing the blog because I wanted to share the interesting things I was seeing in Spain and Portugal. I also wanted to understand what artists here care about, what their challenges and motivations are. So when I travel I look up artists and ask if we can meet in their studios. It is a huge privilege for me to enter another artist’s world like that, and folks here have been very generous. I’ve also been so fortunate to meet the curator and writer Ángel Calvo Ulloa and the artists Cristina Regadas and José Almeida Pereira, who have opened many doors for me here. There’s a lot going on in Madrid, many art worlds, and there’s still so much to learn. I want to keep sharing what I’m seeing, but lately I’ve been drawn into more personal writing projects.

One of the strongest memories I have of you is standing outside the old Axelrad, discussing the future and taking a breath of fresh air from your solo project, A Tension, which was curated by Suplex’s Rachel Vogel. What is it like seeing the evolution of your work from then to now? I guess it only has been two years, but do you approach your practice any differently?

LMF: My experience in the last while has been that a new context can shape what you make and how you think. Galicia and now Madrid have brought out new concerns and imagery. But I wonder if we ever really change the things we want to see. These days I ask myself if the things I want to paint aren’t the things I painted when I was in my teens, or maybe even earlier. It’s hard to say where our preoccupations come from, but I believe in ciphers that we don’t leave and that don’t leave us. They can’t be fully rationalized or explained, and that’s why we keep following them. When I’m researching, writing, or making, I’m in a state of reverence. When I paint here, for example, I’m kneeling on the floor, and it seems fitting- but I think it’s always been this way.

Photo: Cristina Regadas

One of the things I have always admired about your work on paper is the quantity you produce in one series. Do you feel more free producing so many variations of one concept?

LMF: I like working fast. It’s important to make something before you understand why, and even better if the piece still eludes you somehow after finishing. It feels godly to surprise yourself like that. There’s also freedom in looking at a blank surface and exploring it physically. You’re creating a space, but with each mark you’re also fixing an image, so that by making a picture you’re also narrowing the possibilities of what it could be. This is especially true with watercolor, which I use now because it is fast and light. With any kind of making, we are always just trying to get to a closer version of what is already inside of us. So I won’t stop trying again and again.

What medium do you experiment the most with? Is one more challenging than the other?

LMF: Painting and writing feel natural to me but they are also where I take the hardest questions. Painting, when it is working, is transcendent, unlike anything else. Performance is charged, tenuous, and physical: my body and voice are intermediaries between my words and the audience. This is also very transporting. Photography, book making, and video come out when I have the resources. I ask myself where my work belongs and in what mode all the time. Another big question is: how much do I share, and what do I keep just for myself?

I think I am forever grateful to the Menil Collection for capturing your Fabiola performance on tape. Again, another event of yours that I had to watch at a distance. In your talk, you even bring up our first church, St. Catherine of Siena, who by the way is who I am named after. I started crying when you brought it up. But besides all that, I do remember sitting next to you in our Mexican-American Culture class at UH, recalling the way you would recite your papers aloud. It sounded similarly to this performance and in a way I have missed your wisdom. It seems like you always have the right words to describe exactly how you feel. As you reflect on your experiences, what did this performance teach you in the end? In my opinion, you revealed your life and somewhat healed from this talk. Is that true?

LMF: Fabiola was my most profound and my most personal art experience, and I’m still thinking about it. Cindy Peña at the Menil gave me the opportunity to go farther with my work than I’d ever done. I was asking myself about faith, family, romance, and how art touches all of those things. The process of making Fabiola changed me; I was having conversations with artists around me about religion, something I thought was off limits in our world. I was revisiting old memories, old prayers, and old yearnings that had been sleeping inside of me for some time. And I confronted intense questions and emotions that are still overwhelming to grapple with or explain. I’m so touched by people’s responses to the performance and to the artist book. I think most of all I learned that faith is part of me, part of who I was, and who I will be.

Watch Lauren Moya Ford's Fabiola below.

>> Download the transcript

Tell me how you spend your free time in Spain. I think we are all wanting to know.

LMF: This city feels like a treasure chest- there are so many places here filled with precious objects. As a New World person, I’m disconcerted by the finery and the loot, but inevitably I’m also drawn to it; Madrid is a reliquary of many types of knowledge and power. So I visit Madrid’s museums, churches, and libraries. Spending time on trains above or under ground and walking around the city have altered the way I experience time and the way I process things. Being around so many people on foot is humbling, exhilarating, and exhausting. The energy in the streets of this city is all-consuming- it really does not sleep. I like to travel, but Madrid is so intensely centripetal that I haven’t left much. There’s a lot of input here, but I also get so much from exchanging ideas with artists who live in other places. So I spend a good amount of time at home writing, painting, reading, thinking, and making myself tacos, too.

Photo: Cristina Regadas